Throughout history, in all cultures and countries, there has been a constant struggle between innovators and traditionalists.

But how are Tradition and Innovation related? Should they be defined and explored only through their mutual contrast and enmity? Or can they be harmonized into something that incorporates both?

We have no problem with technological innovation. When a new invention or discovery is made, we have no trouble assimilating it into our world. During the Industrial Revolution, for example, where traditional craftsmen and agricultural societies were at odds with the rapid technological advancements and new factories, we saw that eventually the new was accepted because of its utilitarian value. The steamboats and trains, electricity and light bulbs, changed our world in profound ways, but we never felt we needed to defend the stagecoach or the oil-lamp against them! There was no real conflict there. And even where there was initial conflict, as was the case in the seventeenth century, when Galileo had to defend the new Copernican heliocentric view of the universe against the church and other “traditionalists,” the new scientific and technological reality was, as a rule, always accepted (albeit occasionally with considerable delay) because, although it changes our view about the physical world, it has little effect on tradition per se.

But when it comes to social norms and behavior, literature and art, a big conflict appears. Most people, especially the older generations, resist change and innovation. The attachment to what is already familiar and habitual seems difficult to abandon. In cultures like the Indian, Jewish, or Islamic, where tradition lies at the center of society, resistance to innovation and reform tends to be stronger. But even in cultures and civilizations where innovation lay at their very center, like in Ancient Greece, there was a constant struggle between the old and the new. In Ancient Greek theatre, the theme of the old versus the new formed at least part of the plot of a number of tragedies and comedies. In his comedy The Frogs, Aristophanes shows us the two famous tragedians of the day, Aeschylus and Euripides, having a fight: Aeschylus criticizes Euripides for his modern, colloquial style, accusing him of corrupting the audience with newfangled ideas. Euripides argues that he is making drama more relatable and reflective of real life. This back-and-forth debate on stage is full of witty exchanges to which we may easily relate even today; the theme is perennial.

But we need not go that far into the past: Many great theatrical plays and even movies and musicals have exactly this as their main theme. In The Tempest, Shakespeare showcases the conflict between the old world of magic and the era of exploration and reason. Prospero represents a figure torn between the traditional, mystical ways, and the emerging rational world of the Renaissance. This theme is also seen in Cervantes’s Don Quixote, where the old ideals of chivalry clash with the emerging modern world. Similarly, in Turgenev’s Fathers and Sons, we see the generational clash in nineteenth century Russia between the older generation upholding traditional values and the younger generation embracing nihilism and other radical new ideas. The character of Bazarov embodies the spirit of innovation, while his interactions with his family and friends reflect the tension between the old and the new.

One of the best modern expositions of this conflict is to be found in the excellent musical Fiddler on the Roof, where the protagonist, Tevye, a Jewish dairyman in the fictional village of Anatevka in rural Russia, tries to uphold traditional values in a rapidly changing world at the beginning of the twentieth century. The first song in Fiddler on the Roof is “Tradition,” where Tevye introduces the audience to the customs and roles that define life in their village. It sets the stage for the central theme of the musical: the conflict between holding on to traditions and embracing change. His daughters challenge tradition by choosing their husbands for love rather than accepting arranged marriages. Tevye struggles to accept these changes, eventually bending (though not entirely) his strict adherence to tradition for the sake of his daughters’ happiness.

When it comes to art, innovation is even more central than in other fields of life. The whole evolution of art is nothing but the eternal struggle between tradition and innovation. We would never have had a Bach and a Beethoven if we had stayed with monophonic church music. And no Da Vinci, Rembrandt, or Picasso if artists had continued painting medieval church murals and aristocratic portraits. It is through the evolution of art that we may probably find a way to resolve this eternal struggle, for in art we can see clearly how innovation never completely destroys tradition but rather gradually molds it. Let us take Beethoven as our main example:

Beethoven bridged the gap between the Classical and Romantic eras by pushing the boundaries of traditional forms. He took classical structures, like the symphony and sonata, and infused them with greater emotional depth, an expanded harmonic structure, and a new energy. He extended the length and complexity of symphonies, introduced new instruments, and incorporated personal and heroic themes. His willingness to experiment and break the “rules” while still staying within the foundational principles of classicism allowed him to seamlessly integrate tradition with innovation. In his Third Symphony, the “Eroica,” considered by most musicologists to have ushered in the era of Romanticism, he broke new ground in terms of scale, structure, and emotional depth, all while operating within the classical forms. This is why Beethoven is considered to be both the last major composer of the Classical era and the first of the Romantic. He managed to stand on both continents at the same time while creating some of the most revolutionary yet traditional music ever composed!

With Beethoven as our main guide, we may therefore proclaim that:

The best innovation is the one that does not demolish tradition but honors it.

Such innovation springs from the fountain of tradition even as it opens new paths that seem to contradict it. The extent to which an artist innovates while remaining truthful to the principles and soul of his tradition is the measure to which his art becomes the authentic harmonious expression of his culture, life-experiences, and time.

Many other great artists understood this: Picasso, in his groundbreaking 1907 painting “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” drew on traditional African and Iberian art while simultaneously pioneering Cubism, breaking down forms into geometric shapes and presenting multiple perspectives simultaneously. This painting was revolutionary yet rooted in the study of classical and non-Western art traditions.

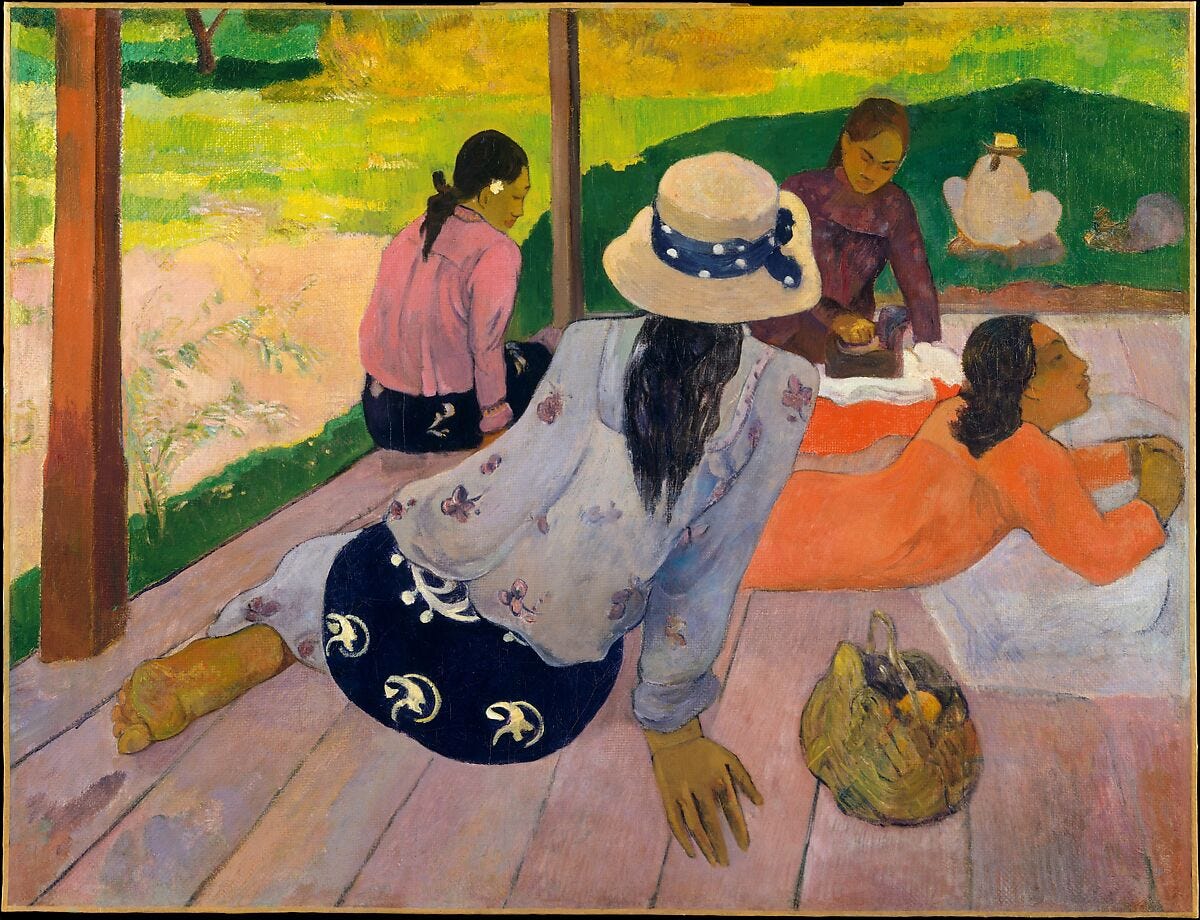

Gauguin is another painter who was not only influenced by the customs of Tahiti, where he lived for a decade, but included them extensively in his art. Some of his greatest works are those that portray Tahitians, Polynesian landscapes, and traditional scenes of everyday life. He also incorporated Polynesian symbols, motifs, and spiritual themes into his work, giving his paintings a unique and exotic quality. Gauguin embraced the Tahitian use of bold colors and simplified forms, which helped him move away from European artistic conventions.

But probably the best example of harmonizing tradition with innovation is to be found on a painting that for many years lived on a large wall in our living room: a framed copy of the Chinese scroll “Along the river during the Qingming Festival,” which is considered the greatest painting of China and which each emperor usually had his artists copy from the previous version. If you compare the various versions of this painting throughout the centuries (the first one was done in the twelfth century), you will see that each one had “improvements” compared to the previous one. The best version is the one currently in Taipei’s National Palace Museum (the copy in our living room) that was commissioned by the artist/poet emperor Qianlong at the beginning in the eighteenth century. Influenced by the use of perspective in European painting, Qianlong’s artists created the illusion of depth and multiple layers, thus making a more realistic representation. It is by incorporating contemporary Western innovations and techniques while keeping the overall philosophy and traditional patterns and themes intact that this supreme synthesis was finally achieved.

But how is the ideal harmonization of Tradition and Innovation to be applied on the level of a modern nation? And are there any modern nations that have achieved it?

Through my extensive travels, I have come to the conclusion that it is possible for a nation that consciously sets out to achieve such a harmony to do so. And there are a few countries that stand above all others in this achievement. One is France. France is the European example par excellence. It has managed to modernize at a very high level without ever losing its traditions and soul. France has the most advanced nuclear power plants in the world and a heavy industry that produces cars, bullet trains, and planes; it excels in design, fashion, cuisine, the production of perfumes, wines, cheeses, and more. Yet at the same time, it preserves its rural weekly farmers’ markets, many annual festivals celebrating local foods, traditional fairs keeping old crafts alive, its regional languages and music such as Breton music in Brittany or Occitan in the south. These traditions are often passed down through generations. The government also encourages all of this with focused policies and much monetary support. France has avoided the fate of most industrialized countries: rural flight. Shockingly, France only has five cities with populations of over half a million, while Germany has fourteen!

It is not by chance that France has the most beautiful villages in the world: “Les Plus Beaux Villages de France” (The Most Beautiful Villages of France) is an exclusive association that recognizes the most picturesque and charming of them in the country. To be included, a village must meet strict criteria. It needs to have a rural character, a population of fewer than 2,000 inhabitants, and at least two protected heritage sites or monuments. Once a village is accepted, it must continue to maintain its standards in periodic reviews. The competition is fierce, because inclusion in the list significantly boosts tourism and local pride. The French cherish their rich cultural heritage while managing to remain a modern industrialized country at the heart of the EU.

Another country that has achieved such a harmony is Japan. In the 50 years following 1868 (the Meiji Restoration), Japan rapidly transformed from a feudal, agrarian society into a modern industrial nation. No other nation has experienced a faster and more disruptive entrance into modernity than Japan. Yet through this monumental (and unique in world history) transformation, Japan managed to preserve its soul. After the huge shock of the first twenty years, the Japanese became mindful of the danger of losing their national character and started returning to their roots. When modernity skews society one-sidedly towards many overwhelming innovations, at which point it starts feeling a strong sense of alienation and a rupture from its roots, an enantiodromia – a balancing act – is set in motion. This is how my friend, author Bill Kelly, describes what happened in his new book The Making of Modern Japan:

By 1890, though, Japanese began to return to their cultural traditions. Many samurai intellectuals who were originally attracted to the West, including some of whom became Christians, had observed the darker side of modern Western civilization. Their familiarity with the West enabled them to achieve a more critical and well-rounded perspective and led to their reexamining of Japanese traditions.

There were several different approaches to uncovering and preserving the cultural treasures of the past. One approach was to search for Japan’s origins as a people and to discover what it truly meant to be Japanese. Folk studies carried out such investigations, and this approach appealed to people who were acutely conscious of the cultural disruption caused by all-out modernization. Through folktales, legends, and the remaining memories about one’s ancestors, the relatively unchanging ways of people in their native places were brought to the attention of modern Japanese. Researchers discovered cultural continuities, providing a glimpse of Japanese roots and “authentic” identity.

Part of this enantiodromia is the occasional invention of new “traditions” that seem old! One notable example is the creation of the “State Shinto” ideology during the Meiji era. While Shinto practices and beliefs were ancient, the new formalized version was largely an invention of the Meiji government that turned it into a state religion to unify the nation and bolster loyalty to the emperor. Practices like visiting Shinto shrines and performing rituals to venerate the emperor as a divine figure were emphasized, creating a sense of national identity that was both traditional and newly formalized. Another example is the Bushido code, or the “way of the warrior.” While the samurai had longstanding martial traditions, the romanticized version of Bushido that we think of today was largely shaped during the early twentieth century.

Such invented traditions are not unique to Japan. Another example is the haka in New Zealand. While the haka is an authentic Māori cultural practice, its use as a pregame ritual by the All Blacks rugby team was popularized in the twentieth century and became a new tradition that now seems timeless but is, in fact, a modern invention.

Bali is another culture that has managed to navigate modernity while keeping its traditions alive. The Balinese have managed to modernize their educational system while incorporating local wisdom, religious teachings, and cultural practices alongside a modern school curriculum. Likewise, traditional Balinese healing practices, such as the use of herbal medicine and holistic therapies, have been integrated into modern medical practices. Another example is the traditional village governance system, which has been adapted to manage modern challenges like tourism and environmental conservation. This is one of the reasons that tourism in Bali has skyrocketed in the past decade: the various Balinese communities are consciously catering to the visitors’ wish to experience an authentic traditional culture within a modern environment. Most importantly, Balinese traditional artisans have adapted their skills to create modern sculpture, paintings, stone and wood carvings, while preserving traditional patterns and methods. Balinese art has never ceased to evolve while residing within its traditional foundations. And of course, despite their incredible wealth of ceremonies, exactly because the Balinese have embraced innovation, they too have their own “invented tradition” that may actually be the most popular of them all: the kecak dance! While it draws on traditional Balinese chants and elements from the Ramayana, this dance as we know it today was actually developed in the 1930s by the German artist Walter Spies and Balinese performers. It was created to present Balinese culture to tourists in a more dramatic and accessible way.

My fourth and final example is Tibetan culture as it is preserved around the world through the leadership of the Dalai Lama. The current Dalai Lama is actually the very embodiment of harmonizing tradition and innovation. He has adopted the most modern ideas in the fields of science, technology, governance … even marketing and advertisement, judging from how much he promotes both his books and his lectures! Having lost his country and being in exile for the last six decades, he has managed to introduce and spread the Tibetan culture, religion, philosophy, and art by establishing Tibetan schools, monasteries, meditation centers, publishing houses, and more around the world. Tibetan Buddhism has in a sense “conquered the world” with the renewed power of this unique civilization. Most recently, the Dalai Lama led a most incredible revolution: He held worldwide democratic elections to replace the theocratic government system of Tibet, in effect destroying a centuries-old tradition and, in so doing, also relinquishing much of his own power!

Tradition and Innovation need not always merely collide. Just as some of the great artists have shown us, and as some of the most successful modern nations have proved, the two can be harmonized into a new whole that incorporates the best of both. Tradition can be integrated into innovation. This is an achievable ideal to which all creators and all nations may aspire. Therefore, we may remove the “versus” in this essay’s title and proclaim:

Innovation within Tradition.

For more Tuesday Letters on Substack, click here.

For more content, visit my website, nicoshadjicostis.com.

Enjoying my Tuesday Letters? Check out my books, available at Amazon.com and at your local bookshop by special order.